Lurid Historical True Crime ... and Why I'm Not An Academic

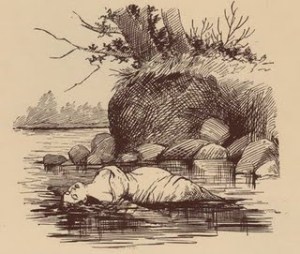

I recently read a couple books about the case of Mary Rogers, a young woman in 19th century New York who was brutally murdered and possibly raped. Or maybe she'd had an abortion and the abortionists disposed of her body in a panic. In any case, she wound up dead in the waters off the shore of New Jersey. There were several different suspects and theories -- a jealous fiance, gang murder, abortion gone wrong? The case was never solved.

The story was a sensation for the burgeoning penny press and inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write the Mystery of Marie Roget, set in Paris but clearly based on the Mary Rogers case. It continues to attract writers as a subject, a classic historical true crime subject.

I recently read a couple books about the case of Mary Rogers, a young woman in 19th century New York who was brutally murdered and possibly raped. Or maybe she'd had an abortion and the abortionists disposed of her body in a panic. In any case, she wound up dead in the waters off the shore of New Jersey. There were several different suspects and theories -- a jealous fiance, gang murder, abortion gone wrong? The case was never solved.

The story was a sensation for the burgeoning penny press and inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write the Mystery of Marie Roget, set in Paris but clearly based on the Mary Rogers case. It continues to attract writers as a subject, a classic historical true crime subject.

The first book I read about it was an academic take: The Mysterious Death of Mary Rogers: Sex and Culture in Nineteenth Century New York. And for an academic book, it was fairly approachable. But I didn't finish it, which is rare for me. Two reasons. The first was the prose, which despite efforts to make the book comprehensible to ordinary humans, still included passages like this:

"As the subject of all forms of social discourse -- the newspaper, the mystery novel, and even that of legislators and reformers -- Rogers was the embodiment of all that antebellum middle-class culture named as unspeakable, but actually, according to the modern critic of the history of sexuality, Foucault, integrated into a 'regulated and polymorphous' variety of discourses."

Someday I will read an academic work in the humanities that does not name-check Foucault and/or Derrida within the first 20 pages. Or maybe I won't, because these works, as a class, are just too annoying. I spent too long in the world of reporting, I guess, but I can't stand being instructed on what something means. Just tell me what happened and let me draw my own conclusions, OK?

The other reason I gave up on this book is I felt there was a fundamental hypocrisy at work. It purports, in passages like that quoted above, to analyze and, to some extent, judge Rogers' treatment as an object of prurience by the press and the public at large. Well, yeah. And why exactly did you choose this subject for your book anyway? Perhaps because you realized that people are fascinated with crime, particularly crimes against attractive young women? Perhaps that's why you also included the word sex in your title? Edgar Allan Poe got it and he didn't feel the need to cast himself as a moral authority who is horrified by other people's interest while he was doing it. Then again, he didn't have Foucault and Derrida to tell him what was really going on.

Speaking of Poe, he is a major player in another nonfiction book about the case which I read all the way through: The Beautiful Cigar Girl by Daniel Stashower. This is a standard work of historical true crime, made sexier by Poe's role in the story. It suffers a bit from the basic problem with the Mary Rogers story -- we never do find out what, exactly, happened to her and who was responsible -- as opposed to other great works of historical true crime, like The Devil in the White City and The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher. Those books give you an answer to what the hell happened. Stashower's book gave me a lot more insight into Poe, so that was a plus. If you're interested in this story or in that genre, I recommend it. The subtitle, I must say, is a bit much: "Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe and the Invention of Murder." I get that you want to get Poe in there. And I get that this case was part of the beginnings of both widespread public interest in crime, via the new popular press. But murder's been around for a long time, hasn't it?

The book I really liked, though, was the one I just finished: The Mystery of Mary Rogers by Rick Geary. It's a graphic novel, part of a series by Geary called A Treasury of Victorian Murder, which also includes famous cases like Lizzie Borden. He's done some 20th century cases, too, and a biography of J. Edgar Hoover. I've now read three of his books and I think they're all terrific. So if you're going to read one book about this case, this one is my recommendation. And if you're a true crime buff, especially a historical true crime buff, definitely check Geary out. They're a good introduction to graphic novels, too, if you're curious about that genre but are not sure where to jump in.