You decide, I read

Every once in awhile I say to myself, hey you lazy self, you should read more classics. * Then a new work of historical fiction or a new season of Justified catches my attention and I conveniently forget.

So now I'm going to take a serious step, the book-reading equivalent of one of those public weight-loss efforts. (No way am I doing that.) I'm going to publicly declare my intention to read a long-neglected classic work of literature. And report back on my progress.

Every once in awhile I say to myself, hey you lazy self, you should read more classics. * Then a new work of historical fiction or a new season of Justified catches my attention and I conveniently forget.

So now I'm going to take a serious step, the book-reading equivalent of one of those public weight-loss efforts. (No way am I doing that.) I'm going to publicly declare my intention to read a long-neglected classic work of literature. And report back on my progress.

To make this even more fun, I decided my summer classic read should be significant. No slim little Dostoyevsky for me. My classic is going to be a Capital C Classic, at least 500 pages, capable of stopping a door in its original hardcover form.

And you're going to choose it for me. I came up with four titles, all books that I should have read by now. But haven't. Here's my understanding of what each book is about.

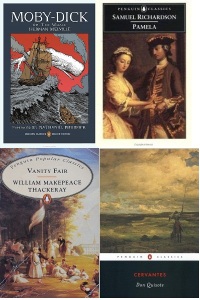

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville: Man chases after whale. 1851, American

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes: Man tilts at windmills. 1605, Spanish

Pamela by Samuel Richardson: Young woman resists employer's son's advances. 1740, English

Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray: Woman claws her way up social ranks. 1847, English

Please vote!

[polldaddy poll=6063734]

* Just for the record I came up with this idea -- even drafted this blog post -- BEFORE the much-circulated Slow Books Manifesto that appeared on the Atlantic website. Modeled on Michael Pollan's rules for eating, it proclaims that we should "Read books. As often as we can. Mostly classics." At least it was much-discussed in library circles. I get what she's saying and I am feeling the need, obviously, for a little more classic fiber in my reading diet. But on the whole I agree with the reply of Seattle Public Library's David Wright, which I'm reposting beyond the jump here. It's a long reply but it's worth reading. Wright, by the way, is one of the authors of SPL's Shelf Talk blog, which is always a worthwhile read.

David Wright reply to the Slow Books Manifesto:

The basic error of this and all those other read-this-not-that pieces that pop up endlessly like nasty looks on a bus is that they so utterly fail to understand all the various things that reading is and does, attempting to valorize so-called “self-improvement” over all the other vital, crucial reasons that we read and consume stories and engage in literary acts. We read for a marvelous variety of reasons, none of them illegitimate or unhealthy. The precise analogy is “sex is for procreation only,” which is a laughable, ultimately futile but possibly quite harmful thing to go around preaching, as it can lead to people with an unhealthy or overly narrow or proscribed view of what sex/reading is, and is for. It turns pleasures into guilty ones, and turns off potential readers who come to feel that books are a matter of should and ought, rather than something living breathing people do for the joy of it. Better to go to a movie.

Having started with this faulty foundation, the minister of Good Books will then go on to opine just which sort of books improve us, and which do not, an exercise so fraught with serious nonsense, received notions, academic claptrap, cultural bullying, and opinions touted as fact as to be laughable, if – again – it weren’t so potentially harmful to would-be readers. Kelly doesn’t have much of a go at this, but what little thinking there is here is entirely unexamined.

The equation of popular reading with junk food is a good old chestnut: back in 1890, in an issue of Library Journal, Herbert Putnam opined about the uselessness of “flabby mental nutriment,” suggesting the only reason for including popular fiction in public libraries was “to attract the reader who has not read at all, or who has formed a taste for only that class of literature and must be tolled by it in order to be wheedled into something better.” He shows his true colors in the next line: “Our American public hardly needs to be wheedled into the reading habit; it reads too many books, not too few.” This was before Movies and TV, which would no doubt have draw his ire had they been around to do so. Many libraries at that time banned fiction altogether at that time, for readers’ own good; William Kite, a librarian in Germantown PA, opined: “A very considerable number of frequenters of our library are factory girls, the class most disposed to seek amusement in novels and peculiarly liable to be injured by their false pictures of life.”

This old-timey paternalism follows the very impulse that motivates Ms. Kelly, and it is nothing new. They sneered at Dickens, with all that Hunger-Games-like mania over Little Nell, and yes, they did look down their noses at Shakespeare with his “little Latin and less Greek,” favoring instead abstruse self-improving Elizabethan prose the likes of which nobody reads today, for very good reason. They tsked at Punch and Judy shows, and inched their way through Anglo Saxon thrillers inserting edifying anachronisms about a Christian God. They shook their heads over Euripides – “Sure, the crowds love him, but he’s certainly no Aeschylus!” – and threw up their hands about the doomed state of literature when a bunch of meddling archaic technogeeks ruined the whole experience by Writing Things Down, in arguments mirrored by anti-audiobook snobs of today.

A good plot-driven story is no more inherently junk food than Woolf, Dickens, Bunyan or Homer. Someone has mentioned Sturgeon’s Law, that 90% of everything, genre or literary, is crap. Truer words were never spoken; the only reason so few readers will confess that they found this or that literary novel or “classic” uniteresting and unworthwhile is that they are cowed by the haughty status of the so-called literary. “Isn’t it supposed to be boring?” I once heard someone say.

I’m a librarian of the sort of works with and talks with readers all the livelong day; readers of every stripe, self-proclaimed snobs and so-called philistines; voracious genre fans who read books by the armload, and precious book group readers who read precisely one book a month, and don’t much like most of them; readers who seek out the classics because they love them, and readers who seek out the classics because they feel it a duty. And many novice readers who are bewildered and even intimidated by the world of books and reading, but something happened and all their friends were reading this year’s mega-hit, and they read it too, and lo and behold, they LIKED it. I pray that such novice readers steer clear of narrow proscriptions like the one in this piece. And they do – in droves. The only reason not to get too het up over this kind of thing is that it is always ignored, and all different sorts of people continue to find all different sorts of books in all different sorts of ways, for all different sorts of reasons. The best book on reading I ever read is Daniel Pennac’s “Better than Life,” which is the original source of a delightful counter-manifesto to this one, called the Reader’s Bill of Rights. Look it up – its great.

As for anyone who tells you to read this, not that, I suggest you tell them – in whatever register is appropriate to the situation – to kindly piss off and mind their own business.